Place Attachment

Place attachment has many definitions. Altman & Low (1992) define place attachment as 'the bond of people to places'. This concept is further elaborated by Brown & Perkins (1992) as 'positively experienced bonds that individuals and groups form with sociophysical environments, which grow from behavioral, cognitive, and affective ties.'

My work is deeply inspired by the connection people have with their homes. My research began by exploring the challenges in Australian housing solutions that possibly hinder deeper place attachment and a sense of belonging.

The tripartite model of place attachment (Scannell & Gifford, 2010)

Research indicates that the social aspect of place attachment is stronger than the physical aspect, with greater attachment observed at the home and city levels compared to the neighbourhood level (Scannell & Gifford, 2010). However, a stronger physical attachment, or “rootedness,” was predicted based on the length of residence, ownership, and plans to stay (Riger and Lavrakas 1981, as cited in Scannell & Gifford, 2010).

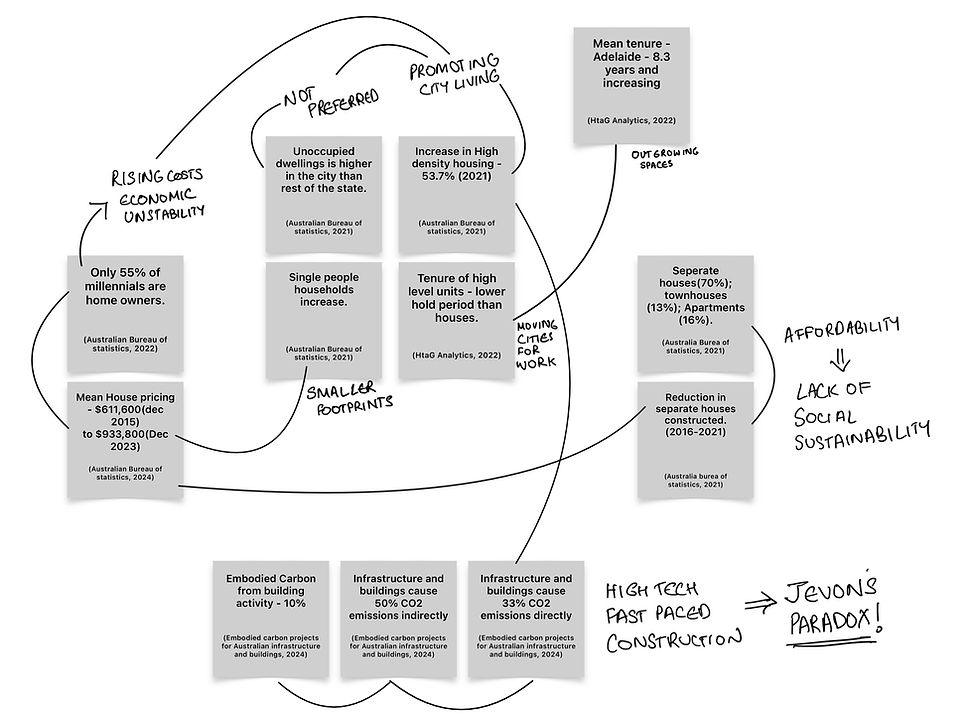

Observing the housing trends and related data in South Australia, through abductive reasoning, I have reached the following conclusions:

I think the rise in high-density living is being driven by an increase in single-person households, reduced home footprints, and affordability pressures. In an attempt to meet the growing demand, efficient fast paced construction may lead to higher carbon emissions.

I also think the higher number of unoccupied dwellings in the city compared to the rest of the state may reflect a growing preference for surburban living, possibly due to lifestyle choices or housing constraints in urban areas.

Relatively shorter tenures in apartments and units (compared to 8.3 years mean in adelaide) suggests that people may be outgrowing their homes and relocating frequently, due to work or changing life circumstances.

This creates an opportunity to rethink a housing solution that can be sustainable and adaptable that may increase tenure and foster a deeper place attachment and a sense of belonging.

VISION

To design a holistically sustainable alternative medium-density housing typology that fosters deeper place attachment through low-tech, sustainable building methods and low-embodied-energy materials.

Sustainability Aims

EARTH ARCHITECTURE

x

Make

By prioritizing low-embodied energy and low-tech construction materials, the design emphasizes the inherent beauty of raw materials, promoting environmental sustainability.

Material Selection: Rammed earth (sourced on-site, assuming soil suitability) and sustainably harvested timber form the primary building materials, ensuring a low-carbon footprint.

ADAPTABILITY

x

Focus

The project balances initial investment with long-term economic sustainability, ensuring affordability and resilience over time.

Adaptive Growth: Homes are designed to be built for immediate needs, giving residents agency to customise their internal layouts, with provisions for future expansion as required.

PLACE ATTACHMENT

x

Achieve

Community well-being is at the heart of the project, fostering social sustainability through shared experiences, and a deep environmental connection.

Community building: The design fosters a sense of place attachment through shared co-working spaces and communal gardens that encourage interaction and collaboration.

Research

PLACE ATTACHMENT

Social aspect is stronger than the physical aspect, with greater attachment observed at the home and city levels compared to the neighbourhood level (Scannell & Gifford, 2010). Stronger physical attachment was predicted based on the length of residence and ownership (Riger and Lavrakas 1981)

EARTH ARCHITECTURE

Rammed RCA reduced 57% to 73% GHG vs conventional brick veneer and cavity brick construction

(Arrigoni et al., 2017).

ADAPTABILITY

Shearing Layers of change. Introduced by architect Frank Duffy and popularized by Stewart Brand. Different rates of change for different layers of the building.

STUDIO WORK

This project adapts a strategic systems thinking approach based on the Baugruppen model, originated in Germany, to facilitate a co-design model between clients, architects, landscape designers, and interior designers. The design development is informed by the shearing layers of change framework and proposes methods of adaptability, and considers the circularity of materials.

Shearing Layers of Change

The shearing layers framework, introduced by Frank Duffy and popularised in How Buildings Learn: What Happens After They're Built, by Steward Brand, explores how different components of a building change at different rates over time.

This concept has been fundamental in interrogating the design, especially to ensure future adaptability and exploring the transient nature of the space plan and services layers.

Underlying Principles

Through a focus on building a sustainable future, the underlying principles propose strategies to challenge conventional practices, offering scalable pathways to systemic change.

New Business Models

Enabling collaborative development and long term value creation that prioritises people and planet over profit.

Modularity

To support efficient, scalable, and resource-conscious decisons for resilient systems.

Circularity

Through material intelligence and embedding re-use poential from the inception.